The Three Ages of Olympic Logos

Everyone loves a new, public logo. It’s a polarising icon, and comments are free. So it is with Olympic logos. Deep Design seeks not to praise or bury them, but to discover the meaning interred into their bones.

Olympic logos support a strong, coherent brand, adapting its unchanging core to a dynamic world. The logos are only one of the brand’s elements, but crucial in a media driven world. The five rings, the flame, torch relays, Olympic villages, and the marathon all effectively emote the Greek myth romanticised by Pierre de Coubertin, the comity of nations and the ideal of human potential.

But Olympic logos have another job. A successful Olympics bid is a high stake win, a sign of alpha-nationhood. Issues of national identity, overt or subliminal, matter. Equally, the fashions, and the design ideologies of the time leave their print on the logos.

Issues of national identity, the fashions, and the design ideologies of the time leave their print on the logos

So do other nations. Logos seems to follow their predecessor’s example, until one makes a huge change. Much like evolution’s Punctuated Equilibrium hypothesis, periods of stability and periods of rapid change alternate. They thus fall neatly into three ages: Nationhood, Modernism, and the New Age.

Through all these, Deep Design, armed with hindsight, reveals the grand theme: the changing place of the Olympics in our lives and the logo as a sign of adaptation.

Here’s the parade; only summer games are included.

The Age of Nationhood, logos from 1924 to 1956

LEFT: Rome 1960‘s she-wolf with the witty Roman numerals stands out from a bunch of bureaucratic logos, and by using grayscale tonality, heralds the age of television. ••• Clockwise, from left: Rome 1960, Paris 1924, Melbourne 1956, Berlin 1936, Helsinki 1952, London 1948 and Los Angeles 1932

In an age of unprecedented acceleration in design, art, and modernity, Olympic logos are in denial. Sternly bureaucratic and monotone, they impose (quasi) national insignia upon the Games.

Sternly bureaucratic and monotone, they impose (quasi) national insignia upon the Games

By 1924, Chanel’s timelessly modern fashion and cosmetics are on the street; even the iconic Noº 5 perfume. But art’s capital city chooses its 14th C coat of arms, depicting maritime trade in Paris 1924. Vibrant USA gives us Los Angeles 1932, as if a police department had married an Ivy League college shield, whose Latin motto on scrolls reveal a yearning for antiquity. The land of Bauhaus, instead presents the Third Reich in Berlin 1936, its eagle oppressing the Olympic rings. The London 1948 Games seek to restore calm after WWII, with Westminster’s bureaucratic stiff upper lip. Helsinki 1952 at least shows off new architecture, but Melbourne 1956’s label-like logo reverts to type.

By 1924, many of Chanel’s timelessly modern cosmetics and garments had been launched, such as the iconic Noº5 and Noº22 perfumes (third and fourth, clockwise from left). Picasso, Braque and Matisse were at large too!

But Rome 1960 represents a thawing. It refers to culture for the first time, picturing the legend of the Rome (not Italy). Its feral snarl is oddly modern and its 3D treatment a tribute to both classical bas-reliefs and Hollywood styling (as in Ben Hur, 1959). The Roman numerals (what else?) bring a smile. Appropriately, it’s on TV for the first time.

The Age of Modernism, logos from 1960-1988

Of the modernist logos, Moscow 1980 and Los Angeles 1932 feel more patriotic than the rest, despite Tokyo 1964’s prominent use of the rising sun that appears on its flag

The Tokyo 1964 Rising Sun is a national symbol used as a geometric element. By doing so, it allows the design to be read as a modernist work, rather than a patriotic symbol from the previous age. It also shows Japan’s confidence in not projecting an overtly cultural identity. This is unlike the other Asian miracle economies of S Korea and China in the coming decades.

Like Japan, Japanese Modernism was a force to reckon with by 1960. Clockwise from left: The Tokyo 1964 logo, Takashi Ono; Nakagin Capsule Tower, Tokyo, Kurokawa Kisyo, 1972; detail from a poster, Ikko Tanaka; detail of poster, Ysaku Kamekura

Abruptly, it unleashes Modernist design, as if a dam had burst. It features geometric abstraction and a minimalist ethic that mutes national symbols and history, and subtracts ornament. Also born: the age of corporate identity and design professionalism. From now, designers would be named, and ‘visual systems’ with manuals would become the norm for large projects, giving the practice a technocratic flavour. (Not coincidentally, this is also the age of Milton Glaser, whose ratings of the logos appear at the end of the article; Tokyo 1964 is his gold medalist).

Abruptly, it unleashes Modernist design. It features geometric abstraction and a minimalist ethic that mutes national symbols and history, and subtracts ornament

Mexico 1968, a modern classic, is the first Olympic wordmark. Its design grid is formed around the five rings, but also draws on early Mexican art and op-art, joining part of the 1960s zeitgeist. Munich 1972 eliminates the Olympic rings. The severe abstraction of the sun and spiral form may not, though, live up to its idea of the “Cheerful Games”. Montreal 1976 is typical too.

Munich 1972 may have been designed in the late 1960s, when psychedelic and Op-Art themes were rampant. Clockwise from left: Munich 1972 logo, Otl Eicher; a detail from Current, Bridget Riley; detail from brochure, Herbert W Kapitzki; detail from Olympic Manual.

The cold war superpowers’ symbols appear more patriotic than others in this cohort. Moscow 1980’s shot at modernism is topped by its red star, and LA 1984 reprises a familiar theme, with its own stars, only moderately modern, with a classic touch. Star wars, surely? In this sense Seoul 1988 is an outlier that hands over to the next age, with a vibrant, but modern depiction of a Taoist cosmology, a universe from which creation springs.

New Age Olympism, logos from 1992 to 2016

The London 2012 logo, (second, clockwise from left) features pink for the first time. De Coubertin in 1912, introduced the six Olympic colours which he said covered all the flags ‘without exception’, calling the five rings a ‘truly international symbol’.

Maybe it was the tearing down of the Berlin Wall, the collapse of the Soviet Union, and the fade of the cold war that caused this change. But Deep Design, remembering that even causes have causes, is a cautious theoriser, and sticks to what’s observable.

Flowing free forms. human figures and hand-drawn artwork show a fatigue with modernism’s technological side. Equally, a fatigue with ideals, and a populist desire to bring the Games down from the heights of Mount Olympus, make them human, not godly, to be celebrated, not looked up to. Everyone’s invited.

Desire to bring the Games down from the heights of Mount Olympus, make them human, not godly, to be celebrated, not looked up to. Everyone’s invited

Barcelona 1992 takes the leap. Its designers say that.‘…the symbol could not be made with a …geometric or technological vocabulary.’ Atlanta 1996’s centennial flame, is playful, not prayerful, and the stars even twinkle. Sydney 2000 reduces the Opera House to a sketch, and rides a boomerang. Athens 2004 reintroduces the wreath in the medal ceremony, but with casual flair. Beijing 2008 visually puns the character for ‘culture’ with a human figure. London 2012’s aggressive logo pumps out a megawatt heavy-metal party, painting the Olympics magenta (not part of de Coubertin’s 1912 Olympic palette, which covered the flags of all nations ‘without exception’). In Rio 2016 the comity of nations becomes a sophisticated carnival in an in-vogue 3D style. Does Tokyo 2020 start something new? Look up Deep Design in 2032.

Clockwise, from left: Rio 2016 logo by Brazilian agency Tatil; detail of Telko logo, showing 3D themes then in vogue; Dance, Henri Matisse, a possible inspiration; Heydar Aliyev Centre, by Zaha Hadid, Azerbaijan 2012.

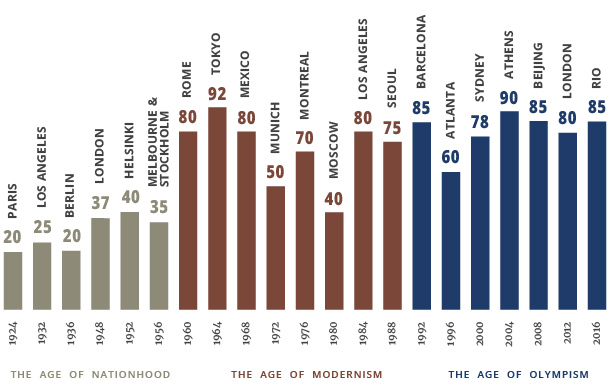

Milton Glaser, legendary Graphic designer, ranked Olympic logos. Though his marking scheme is not known, Glaser judges their success in professional terms: logos should be understandable, memorable and formalistically attractive.

Podium Finish: Milton Glaser’s approval ratings, 0–100

______________________

First published in a slightly modified form in Business Standard, 13 August, in Deep Design, a fortnightly column by Itu Chaudhuri.