Design to Consumer: I’m Not Sure We’ve Met?

Design, properly understood, is inherently social. Designers make objects and symbols, for the eventual use of other people, to fit into, or sometimes transform socially determined situations. So an invitation to ‘share a fresh perspective’ at a consumer summit, to an audience of marketers, should hardly have caused unease.

But inquiry is born from unease; in this case, from Deep Design’s dawning realisation that designers don’t really deal with consumers. They aren’t trained for it.

Marketers and designers want to work together more closely, but they lack a common view of the humanscape. Wherever the marketer can speak for the consumer, he has the mike, so to speak.

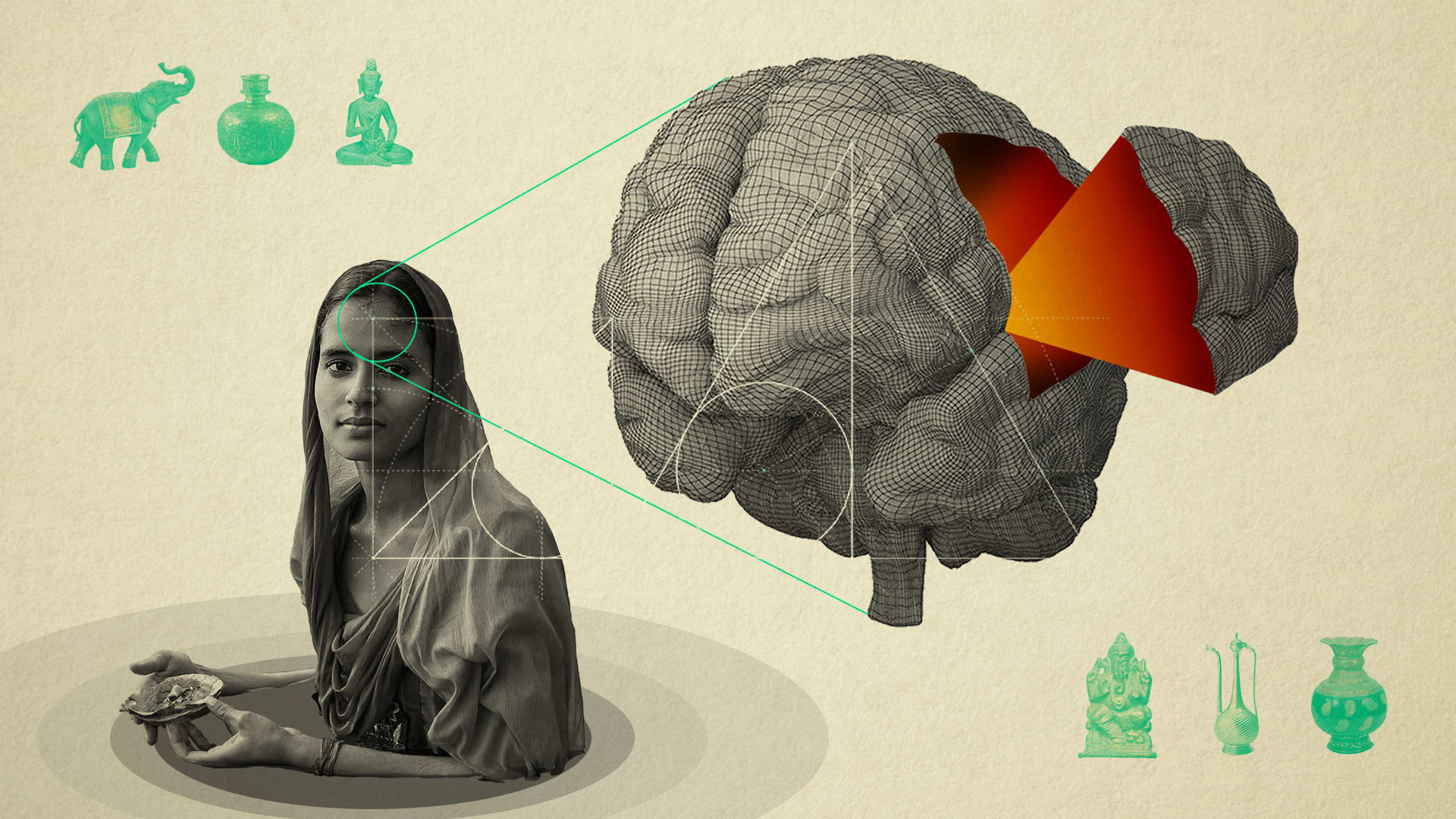

Design, to use the current argot of the trade, is centred on users, or humans—a carpenter using a drill, a reader scanning a newspaper page, book or website, a mother manoeuvring her toddler into a high chair. It addresses the unchanging human system: the body and its limbs; a sensory apparatus dominated by sight; a logical tendency, subject to a fickle attention and the twitches of the lizard brain; perhaps some rudimentary notions of pride.

Finally, design’s problem-solving orientation focuses on the user’s behaviour in the context of interacting with the designed solution, not an inner drive. We care about a score of things: from whether her task got done, to whether our work left society better in some way. But not whether this user was insecure about her future, socially constrained, or struggling with being modern: a user is a user.

Joy to the world, the consumer is born

Advertising created the consumer, or a person viewed purely by a propensity to buy, use up, and buy more of something, when industrial capitalism started to produce increasingly better but increasingly similar products. Human ingenuity responded by creating new needs, (like the ability to impress friends at a party) and fears, (like the failure to be a good mum). Not much design here; and while the human traits assumed here are fairly universal, it does introduce psychology into the mix.

More sophisticated efforts from the time of Cheskin’s sensory marketing have co-opted design, realising that a product’s visual imprint can transcend its function. These marketers were not just after simple beauty, but saw form as whispering to a consumer psyche, per the psychological fashions of the day. So Bernays’ stunt of getting suffragettes to simultaneously light up cigarettes, during a march down a Manhattan avenue, was meant to convince women to overcome their unconscious (Freudian) fear of the cigarette’s ‘phallic’ shape. Post-war American cars were endlessly re-designed, to engineer their appearance to work with the consumer’s hidden mental apparatus, arguably to appeal to masculinity and power.

But consumer theory is a braid with two strands. One strand is empirical, quantitative and cognitive. It aims to tease out the best approach to (for example) segmenting markets, studying things like demographics, spending power, geography, and physical constraints to buying. Rather like applied economics, it deals with the consumer’s rational side, offering benefits like efficacy or economy that are universal. Complexity notwithstanding, a great deal can be made out by careful statistics and reason working hand in hand, to some degree of certainty.

(L-R) Post-war American cars endlessly re-designed, to engineer their appearance to appeal to masculinity and power; Alessi’ best known classic ‘kettle’; Bon Ami cleanser print advertisement; Bernay’s ‘Torches of Freedom’ stunt at the Easter Parade

I have a feeling

The other strand hypothesises the consumer as an emotional being who is an actor in a social, cultural and economic drama, to explain or identify her deep motivations and anxieties. It uses data, but interpretively, and also pays heed to trained impressions. Its findings are qualitative and uncertain. It seeks validity, postponing the need for certainty.

Of particular interest are the consumer’s values and culture. This is an attempt to extend our knowledge of the consumer including but beyond his observed behaviour in the context of our product or brand, but a deep orientation that influences his actions, at various if not all times. The idea is that a brand’s values can resonate with that of a group of consumers, and make them loyalists. (Go back to paragraph 3 and appreciate the contrast).

These groupings offer a kind of alternate market segmentation, cutting across income classes, social class lines (defined by entitlements like access and status) or communal ones (such as religious, ethnic or national). For example: the multitudes that see in a Trump or a Modi a corrective to a historical power grab by a mealy-mouthed elite. Or others who belatedly learn ritualism from a previous generation to compensate for the Indian-ness they see evaporating from their lives. Each grouping, united by attitude, offers multiple predictions, not for a single, narrow product or context, but with multiple economic, social, cultural and political possibilities, with lasting implications.

Design speaks up

It is in this second strand that designers can come into their own, not in their accustomed role as downstream providers of expression, who take their cues from marketers. Instead, as intelligent observers and interpreters of culture, especially the visual. They are uniquely placed because they pour products into the stream of culture, as well as fish in it for reference and inspiration.

Designers can observe how people express themselves visually: the fashions and codes their choices seem to converge on. How we decorate our homes (why is a comic book style print of Meena Kumari doing on that cushion cover?), and how the groom’s niece dances at a sangeet function, why not? And yes, how they buy. Then, they need to join the dots: what does this say about people and their responses the forces shaping their life? The anthropologist Grant McCracken, who studies culture and commerce, sees this as the source of design’s power in the boardroom.

Alessi is more

Or take the Italian household appliances maker Alessi, which commissions famous designers for its products, and has several iconic products among them. The business scholar Roberto Verganti, who has studied the methods of innovative Italian businesses, points out that these icons are not merely awards-circuit darlings but broad commercial successes. They command significant price premiums and disproportionate volumes, for years together. That last criterion implies deep attachment, not an acute social contagion with a brief, steep peak.

Alessi’s method relies on trusted interpreters, who identify large cultural swells (a fatigue with a joyless modernity, for example) and select a designer based on the likelihood that his temperament can speak to that mood. Their choices may be surprising: Alessi’s best known classic, a kettle, came out of a collaboration with the American architect Michael Graves.

The challenge for marketers with this type of thinking is to tolerate the uncertainty of a payoff, in exchange for its size and longevity. Innovative products or market strategies need more than a jaap of the Steve Jobs naam. Designers need to be able to not just observe and imagine, but to convincingly interpret and act. They can start by convincing themselves. So, I accepted the invitation. Will you?

______________________

First published in a slightly modified form ‘Design to consumer: I’m not sure we’ve met?’ in Business Standard, 18 March, in Deep Design, a fortnightly column by Itu Chaudhuri.