Eyes Wide Open: A travelogue celebrating design in Helsinki

Itu Chaudhuri writes for Outlook Traveller on his visit to Helsinki, the World Design Capital 2012. This piece was carried in the August 2010 issue.

You already know Finland, though you may not know you know. There’s so much above the surface, rather than hidden below, that you can miss it altogether. Take my story, for instance. I was to cover Helsinki as a holiday destination, but as a designer, determined to look below the surface, and uncover it instead. As the World Design Capital 2012, perhaps, or as a pilgrimage to intelligence and beauty. I needn’t have, and you shouldn’t either. Just stay on the surface and the deep design at its core will search you out instead.

Finnair deposits us at Helsinki airport one crisp blue morning. The immediate impression: typical European capital, superbly functional and pretty, with heritage buildings still in use, the streets host to an outstandingly usable tram/bus system, not overrun by cars; yet, highly walkable and, as a bonus, English is spoken everywhere. The airport bus drops us off at the railway terminus, and right away, Helsinki starts to leave its stamp. One, this isn’t just any terminus. Put your bags down and look. It’s a landmark, both for the city, and in modern Helsinki’s architectural history. It is classical, but more modern than its 1909 date suggests, reassuring and stimulating at once. Its synthesis of styles recalls, not the gothic excesses of Mumbai’s VT, but the 1920s New Delhi of Lutyens and Baker. It’s small, as the rail hub for all of Finland’s five million people, perhaps as many as VT. Then, I notice the area is named Eliel, and smile. For Eliel Saarinen is no president or general, no bronze figure on a horse, but the building’s architect, and clearly a Finnish icon.

Once in our rooms, we find the itineraries that the tourist board has left for us. Call it coincidence or conspiracy, but I doubt if in another country our first stop would be a design museum rather than one that houses its art treasures. The museum is a revelation, but not for the usual reasons. For one, not many cities have a museum devoted to design. London’s is a mere token in comparison, while Zürich’s is stellar, and some few biggies have worthwhile sections on design (New York’s MOMA, London’s V&A, notably). But while these present design as a sub-plot in the story of civilisation, Helsinki’s turns out to be an exercise in national identity building.

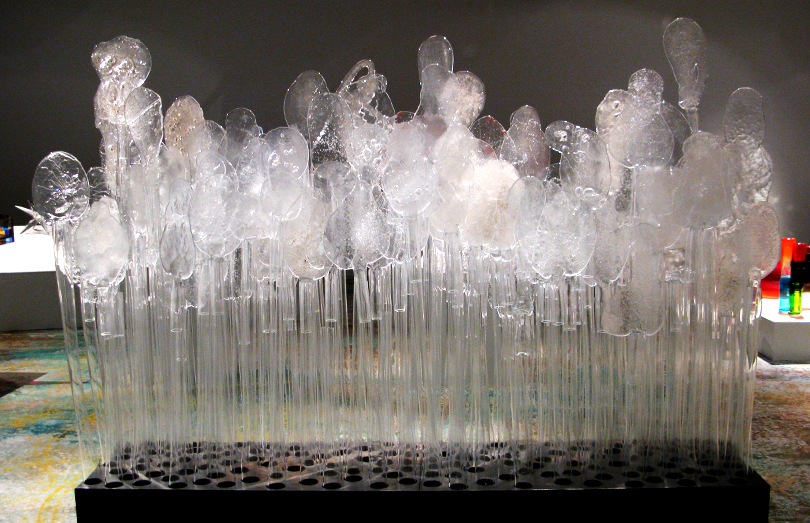

Housed in a 19th century building, the permanent exhibit tells the story of Finnish design in a way that makes it clear where the national ego is invested. You are present at the birth of modern Finland, as it drew on its craft traditions and moved to its industrial present. You see that many of the world’s iconic objects are part of everyday life for Finns. Fabric, chairs, many of them signposts in design history; the development of Finland’s internationally known firms, spanning three centuries; the clothing label made famous by a pregnant Jacqueline Kennedy on the cover of Time; lamps, telephones, electronics. The permanent exhibit lights up Finland for us, but it’s the current exhibit, featuring the glass pieces of Oiva Toikka, the doyen of a long line of Finnish masters in glass, that’s truly incandescent. ‘Everyday’ art, like his birds, which can be bought from outlets, sits alongside his pure sculpture. The inventiveness and panache pierce the eye, mind and heart. There’s almost always one like it, so this is one museum that is definitely worth your time.

It’s 10:30 pm at Casa Largo, one of the city’s many tapas bars, and we’re putting away chorizos and beer (the local wheat beer, quite good). Helsinki’s restaurants are competent, low-key and a tad friendlier than elsewhere on the continent, so it’s easy to relax and reflect. We talk into the endless evening. Soon the sun will set, and the short night will fill with a luminous blue—bright enough to read a newspaper headline by—for in peak summer, the northern latitudes never blackout. Like the genius of Finland’s designers, I think, as the beer does its work, and allows fancies to foam to the top. Let’s see: Toikka’s glass wonders will never lose their colours, this is a physical fact. And those design classics from 40 years ago will be permanently modern and beautiful, evading age like the Helsinki evening resists the dark night. Last chorizo…

It’s an early start the next morning, following a tough day: 22 hours between airports, museums, streets and dinner. The trick is to fly far into the north, and gain three-and-half hours going west at the same time.

I stumble out of bed at 4:30 am for a drink of water, and discover an eight-foot tall, impossibly thin lamp standing in our room, marvellously vertical and dazzling. A gift from the design museum folk, surely; that’s excessive, and how will it travel back with us? In the first seconds of waking, I walk towards it, part the crack in the curtains where the lamp stood: it’s day outside. As magical as the gift that wasn’t.

The early start is for a sponsor shoot, of the airport’s spa and business lounge. Superb as they are, an obligation is never pure pleasure, but there’s a gem here, too. It’s set into a three milimetre hole in a tabletop in the frequent-flyer lounge. Just leave your mobile on the table, and it’ll charge the battery, without wires, via a little adapter (future phones won’t need one). We have no photograph. All you see is a blue glow.

Our lunch date is on the Esplanadi. It runs east-west, like a little equator, and is a good way to mentally map this very compact city. It’s two one-way lanes with 200 feet of shaded garden in between, where you’d expect the trams to be. Walk among the picnicking families and the gulls, and past the patinaed statue of Runenberg, Finland’s national poet. The boutiques, cafés and stores on either side, and on the streets running off it, are among the city’s most stylish. And important, for the design icons are there: Iittala, the glassware icon is also selling

Toikka’s glass birds; Marimekko (textiles, ceramics, clothing) is always worth a look, as are many others. Gawk, shop, eat; the Esplanadi is great shorthand for what Helsinki offers the lazy traveller.

The Esplanadi’s east end has the market square, and the sea. For the reader who, despite my pleading, finds Helsinki grey, orderly and cool to the touch—here is relief. Fabulous veggies, flowers sell briskly beneath the red plastic tarps that make up the shops, packed close together; crêpes fly off the pan, porcelain jewellery (some of it excellent) and curios (rubbish, at last!) do well here. Bargaining is expected, several tongues heard—Estonian from just across the sea—and a little of New Delhi’s Janpath provided by a Tibetan family. There is casualness here, though disorder there is not, a gentle bustle, never quite a crowd; just evidence of a beating heart.

You already know Finnish design, of course, just that you don’t know you know. It’s influence is everywhere around you, in the furniture of the chic home, though you must travel here to realise this. Or try this: perhaps you use a Nokia phone, but never thought of the work that’s gone into it as design? Or years ago, discovered Fiskars, the scissors that showed how a superb technical tool could be a joy to look at and use. Or perhaps your company’s website runs on a Linux server, written—designed for free public use—by a Finnish genius.

I’m thinking these thoughts on a tram to the whimsically named Arabia (a-rah-bia), Finland’s 130-year-old ceramics giant. It’s a long ride by local standards, about 30 minutes. Fiskars, they of the jolly orange scissors, owns Arabia and the glassware brand Iittala. It’s a vast complex, and is open for public viewing.

Arabia is what Hitkari Potteries could have been, but isn’t, for reasons that become clear soon. Its premises host some of Finland’s best ceramic artist-designers, not as employees, but as artists-in-residence. It is symbiotic: artists are free to pursue their own art, without obligation to Arabia, which provides studios and technical support. Arabia gains from its association with art and, when the artists agree, from their design services, employed to co-develop commercial products. There’s a guided Arabia tour, and you can buy all the Fiskars group stuff from the factory store at a discount. It’s everyday ware, and those who see meaning in the proportion, form and detail of a teacup or a dish will find a quiet joy in these, a subtle glow rather than dazzle. These aren’t heirlooms; they’re yours to use, today. As an Iittala ad says, “it’s what’s inside that makes it yours”.

The Arabia visit—was it the heat from the kilns?—has baked the thoughts of these past days into a manifesto for Finland. Museum and store are one. Artist and designer are one; the craftsman is both. Design is for everyone, to be bought and loved; you are a real artist if your work is for me to love and use. The self-given tag, ‘design society’, is no idle boast. Perhaps this is best illustrated by the posthumous presence of Finland’s great modernist architect Alvar Aalto (1898-1976). Worshipped—I choose this word carefully—for placing the country, via design, on the world map. His career mirrors Finland’s decades of growth and industrialisation.

Aalto’s visage has been on Finnish currency notes and postage stamps; he has, arguably, the world’s most important architecture award named for him, and a university. His studio home is preserved as a virtual shrine, which you must enter unshod, and soft-foot around with reverential Japanese architects for company. But unless you are paying homage, give it a miss. You may also see several of his buildings in Helsinki, if Nordic modernism is your thing—or you may not. But do not, on any account, miss the Artek store, started by Aalto, on the Esplanadi’s north side. Aalto-designed furniture, lamps and vases, as well as work by others add up to one of the most thrilling displays of modernist furniture and design you’ll see anywhere in the world. And yes, they’ll ship. What else is money, and a lot of it, for?

Yes, shopping is a great way to connect with the city’s treasures, if you are not weak of wallet. Else, pretend. One way to do this is to explore the Helsinki Design District, a collection of 190 stores and boutiques, and galleries. It isn’t a geographic district but a ‘state of mind’, as it calls itself—a recognition conferred-upon noteworthy initiatives in design, fashion and art, selected by a local association. You’ll see the logo on the storefront of the anointed places.

The city isn’t all art and technology. Eventually, Helsinki reveals itself best through aimless wandering and inward reflection. Walking about is rewarding. There’s a quirkiness to the heritage architecture, Russian touches here, Greek Orthodox there; or figures from Finnish myths, a menagerie of goblins, good and evil. And it’s easy to forget that a respect for nature and the quiet of the countryside are at the root of Finland’s deep design. Late one afternoon I find all of these in one place, albeit via guided tour, in a church.

In the 1960s, the city decided to locate a neighbourhood church on this massive granite outcrop. The architects carved a circular space out of the rock, adopting the hill’s contours, and leaving the walls bare. A circular roof was mounted above the cave, atop a finned clerestory that bathes the church in filtered light. They finished the ceiling with miles of copper wire, creating a vast, gleaming disc, like a copper lid on a crude stone dish. None of this is revealed by its modest outside. But once inside, the effect is as dramatic as any ancient cathedral and as modern as any building will ever be. Come back next century and see.

I sit on the wooden pews, my mind silenced by the scene. A choir from nearby Estonia has come to visit. They spread out among the crowd and, quite spontaneously, begin practicing their scales. Their power and harmony, in the church’s perfect acoustics, seem to make the roof gleam and sing. And for a long moment, I, atheist, find God in design, the true faith of Finland.