How’s the Josh?

Indian campaigns aren’t really designed in the usual sense, unlike in the US: logos, typefaces and imagery, thoughtfully created and effectively orchestrated. But widen the window of design to view communication, and the effectiveness of Indian campaigns pops into focus.

Consider the campaign as a totality of impressions: actions, statements, media reports, symbolism, and the like. Look beyond the fabulously chaotic visual arena, and attend to the theatres of message and rhetoric. Especially, listen for the unspoken: the signalling, or the suggestions beyond the verbal.

The campaign should include Mr Modi’s last tenure, His governance tends to be in campaign mode: carefully scripted events and messaging.

The winning campaign, defined like this, spoke better to emotion, using reason only to rationalise its appeals. By this reckoning, Mr Modi’s BJP was much the better campaign. Its appeal came from classic visceral, gut-driven methods. It played to the anxieties of millions, not always expressed (except in the last few years).

It sharpened these anxieties by underlining group identities, both of its flock and of its opponents. Moreover, it was coherent, that is, the messages across the ecosystem, from base utterances to presidential statements, reinforces each other and maintained consistency over time. The resulting grand narrative increased their effectiveness.

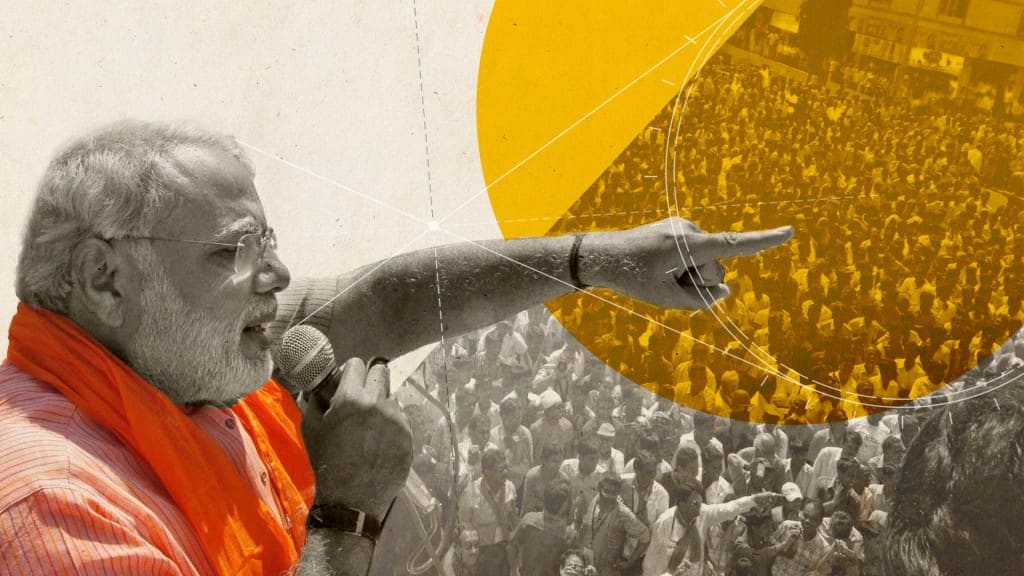

Central to the structure of the Modi-BJP campaign is the strong, muscular and decisive leader as a centrepiece. Populist toughness is the leader’s personal style which eclipses or subsumes the party’s. Tough talk on internal divisions and neighbourly relations was and will be positioned as a necessary antidote to impotent intellectualism.

The responses to the Uri and Pulwama strikes became perfect opportunities to display militarism. The film dramatising Uri became a top grosser. Pulwama’s timing halted the talk of opposition momentum. Personal credit was given and accepted, the strongman won the war.

Just as visceral was demonetisation, a daring display of will, regardless of its economic failure (or success) and its allegedly political intent. The signal is everything: bitter medicine, unconstrained by feeble intellectualising or corrupt interests (the opposition’s two faces). The film portrayal of Manmohan Singh as a weak PM came in handy as contrast.

Identity is tied to this by having the strong-leader-centrepiece represent a broad consensus of the anti-intellectual, unlearned, earthy common-folk, pitted against the previously ruling classes. To them, the speculation that Ganesha’s elephant head suggests ancient plastic surgery might well have been upheld as genuine theistic belief, rather than a lack of science. Likewise the prime-minister’s self-reported intervention, sending in fighters in cloudy weather to evade enemy radar may have demonstrated the victory of audacity and common wisdom over timid technocracy.

Mr Modi was, and is, pictured as celibate, an ascetic, a fakir, and thus a man of sacrifice. TV caught him meditating in a man-made cave, during, naturally, the ‘silent period’. The other side: all family skeletons, and atheism leavened with new-age Buddhism or new-found Hindu-ness.

Identity in this campaign was also signalled by actions that challenged nominal secularism as a criterion for leadership. The religious populism of a Mahant-strongman served as a trishul against other strongmen. Opposed groups were reduced to termites (or to Pakistanis) by various arms of the party machine, allowing a bundling of Muslims and their political support as the enemy.

An identity war needs an enemy. Its figurehead remains the purge-worthy Congress but also a spectrum of civil and political dissenters. Their supporters’ tags are designed to attack both class and politics. Urban Naxals, Lutyen’s types, Tukde-tukde gang, presstitutes—they are of a class foreign to the flock. Chaiwala and the chowkidar sub-campaign were more than deft retorts to a Congress slur in 2014 or a corruption charge this time around. The class resonance is unmistakable, and may have even earned Mr Modi some subaltern sympathy. I (we) are one of you; they are the opposite.

But their opponents were observably foreign in origin. Priyanka Gandhi’s playing with a snake was swiftly recast as oriental entertainment. The tagging of the young Gandhis as both un-Indian and baba-log resonates with earlier mocking references to ‘Italian uncles’, their mother and angrez-minded great-grandfather. This is coherence.

The closest the opposition came to a campaign theme was ‘the idea of India’, which criticised strongman-style nationalism, and purported to protect democratic principles (secularism, tolerance, dissent) and institutions (from universities to central banks) from Modi’s BJP. These abstractions don’t appeal to the visceral instinct. They require Class IX civics and some reflection to appreciate. Rafale corruption flew briefly, but was grounded for technical reasons. The Congress president did try to connect suit-boot ki sarkar to crony capitalism, a start of a coherent theme based on a potent visual (following the PM’s choice of suiting), but couldn’t sustain the connection.

Set against the chatterati’s clucking was the young voter who appeared regularly on evening television. He would admit that his lot is bad, yet underlined his faith in the potency of the national strongman, above his party, for reasons that seemed unnecessary to explain. Gut level feelings like these make or break election campaigns. Reasons are rationalisations, but emotions drive actions.

____________________

First published in a slightly modified form under the title ‘The ‘fakir’ took on the ‘foreigner’, and emotion won the day’.