Requiem for the Music Store

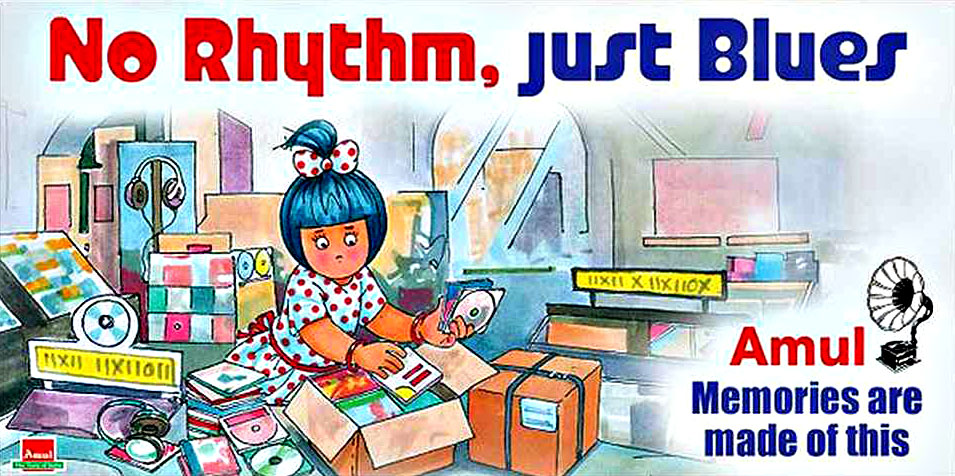

First, the news. On a sad day for music lovers, especially those of the classical kind, the iconic music store Rhythm House, at Kalaghoda in Mumbai, shut down its online ordering service citing “obvious reasons”, in a message on its website on Valentine’s day. The physical shop shut down two months ago.

That’s the end of countless hours spent there by rasiks (aficionados) in listening booths (what are those, you ask?) browsing the aisles, buying even; or chatting with the knowledgeable and charming owner, Mr Carmalli on matters musical; in sum, a superior form of retail therapy. You’ve seen this movie before. Indeed, the shutting down of small charming stores is something of a Hollywood trope. Bookshops and music stores are most typical. Bakeries and restaurants too, but those are usually posed as the conflict of heartless big businesses and small ones (all family and French hearts). What’s new? Nothing, just a chance to reflect on surviving disruption. In which the older you are, the longer you’ll live.

What’s new? Nothing, just a chance to reflect on surviving disruption. In which the older you are, the longer you’ll live.

The writer Nassim Nicholas Taleb suggests that the longer a practice has survived in civilisation, and the more it has to do with slow-changing things like the human senses, the longer it will survive; the more it has to do with social networks, the more fragile its future is to catastrophic change.

Consumption and Commerce, a Two Headed Hammer

Expect, therefore, the consumption of wine and cheese to be robust to change for centuries — we will drink wine from clear glasses, themselves centuries old in form. But its commerce has already changed: Jacob’s Creek and Blue Tail are branded wine companies run like beverage firms, achieving scale and consistent quality, a new business format, while the ‘ideal’ of taste will be very slow, if it will ever, to change.

Rhythm House, and music stores, faced a double whammy. Not digitisation per se, because Rhythm House sold many CDs, and even became a publisher. Recorded music in physical form is just over a century old, while CDs date back to only the 1970s. It’s the de-materialisation of physically sold music, last seen as the CD, and the rise of online listening—commerce too, but crucially, a new mode of consumption—that killed the CD. Blame Apple!

The physical book is about 580 years old, taking Gutenberg’s invention as a start year (early presses, about 70 years later, could crank out 30 copies a month of page-turners filled with lorem ipsum). The disruption to booksellers is more from commerce (amazon.com, for example) than from online consumption (Kindle, for example). Despite ebooks and the Kindle, printed books thrive, even if they are slowing. Maybe one day the Kindle will perfectly mimic the printed book; maybe gradual generational change will kill the bound book. The hype cycle (it’s dead! it’s not! it’s dead!) lives on, but expect a long struggle (wait, 2015 even saw a fall in ebook sales).

Movie theatres: watch (out). The DVD struggles against online watching, but the cinema theatre still hangs in there. I’d speculate that its protection from Netflix is not the picture quality of movie projection but the consumption ritual of watching movies in a communal way, even if with strangers in the dark, and dedicating a time slot entirely to it. This makes it similar to the performance of drama, which is millenniums old (Kalidas wrote 1500 years ago). But only similar…

So Rhythm House had it much worse than a bookstore, many of which have shut down, shrunk, or given themselves over to children’s encyclopedias, self-improvement and management books, and types of books specially crafted to be unsuitable for digital consumption.

Brand as Protection, and a Lament

To survive, Rhythm House would have had to start years earlier and build a business, and a brand, that did and stood for something beyond simply selling music.

I’m not denying that piracy affected it, as it did large music retailers who have shut down too. (Stale whine, says the office wag). But it doesn’t alter the importance of staying ahead of disruption, as Levitt, Clay Christensen and legions of others have pointed out forever. And the importance of branding accordingly.

It’s best to brand, and think, around an idea that’s larger than the originating product: it could be values, benefits, personality or even a core know-how that will outlast the product. (Got one?)

Names aren’t everything, but they do hint at a vision. For adapting to change, names should reflect the brand’s intangible qualities.

Names aren’t everything, but they do hint at a vision. For adapting to change, names should reflect the brand’s intangible qualities.

‘Amazon’ evokes massive-ness in motion, permanence, and vast ambition, not books, which it started with. Flipkart followed the same trajectory, and maybe Flip doesn’t strongly evoke books, but what does Flip mean today? Convenience?

Rhythm House, in contrast, almost translates as ‘music shop’ — a tiny, tangible thing. They tried to disrupt themselves, a very hard thing to do, but didn’t go far or fast enough. Neither did they build themselves the protection of a brand that could birth a new business when the time came. For all that, they are no less loved.