Visionary Position: Design on Top

Look around you and you likely wouldn’t know it, if you are reading this in print in a developing country, but business is getting very, very attracted to design. If, on the other hand, you are reading this on a screen in a G-8 country, this may seem like settled fact. This is a consummation that designers have long and devoutly wished, and while isn’t, not yet, a ‘best practice’ that corporations adore, it’s no longer just conference-room hype. Power and money demonstrate that.

business is getting very, very attracted to design

Let’s start by looking at the shapes this movement has taken. According to a survey of 400+ companies, startups are very likely to have CEOs or CXOs to influence design decisions, and those businesses appear to quantifiably benefit from design.

But top management can go further than being involved in design, and actually invest in it. In 2016, General Electric, an icon of US industry, announced a new headquarters, three-fourths of whose employees would be “digital industrial product managers, designers, and developers”. For a corporate office, that number shows an unprecedented proportion for the design function, broadly defined, and its unusual proximity to the power centre of an industrial company.

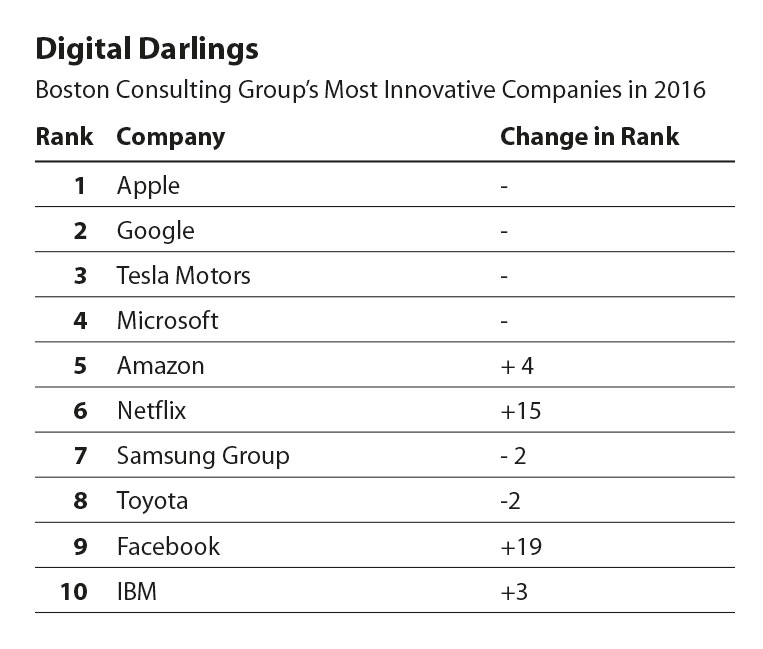

Or it could actually invite designers to the top. Most of the Boston Consulting Group (BCG) 2016 list of most innovative firms has designers and design in positions of power: the likes of Apple, Google, Tesla, Samsung regularly feature on it. Several have designers in the founder group (Airbnb’s Joe Gebbia, Pinterest’s Evan Sharp) or as CEOs. Yet other companies have designations like Chief Design Officer (3M, Apple, PepsiCo, Philips) or Executive Creative Officer, or just Chief Creative.

CDOs, Clockwise Peter Schreyer (KIA and Hyundai), Sean Carney (Philips), Mauro Porcini (PepsiCo), Jonathan Ive (Apple), Eric Quint (3M), Ernesto Quinteros (Johnson & Johnson)

But good businesses have always used design, if not its language. IBM was a design leader decades before today’s design darling, Apple was born. What has changed? An accelerated rise in design consciousness, and concomitantly, its visibility. One can speculate on the causes and the period of this change.

Design has countered commoditisation since at least the 18th century: consider Wedgwood’s famous china ware, a manufactured product carefully designed to meet a series of precise design objectives. To be sure, the same forces of commoditisation keep pace with the thousands of products that appear, washing over them, and making innovation the most prized attribute of modern business. No industry typifies this like information technology.

Wedgwood’s famous china ware

The top ten of BCG’s innovation list concentrates these prodigies in a tight cluster. These companies either make the tools, like Apple or Google, or embed them into their services so completely that firms like Amazon or Uber may be better seen as technology companies than as supermarket or taxi businesses.

Deep Design’s speculation is that this digital breed has given design this status by employing it in a manner that other industries seek to imitate. Design is now seen by the admirers of these digital wunderkind as a synonym or a precursor to the holy grail, innovation. (While there are overlaps, design and innovation are not identical, but more another time).

Design is now seen by the admirers of these digital wunderkind as a synonym or a precursor to the holy grail, innovation.

Boston Consulting Group’s list of ‘Most Innovative Companies’ in 2016 vs. their 2015 rankings

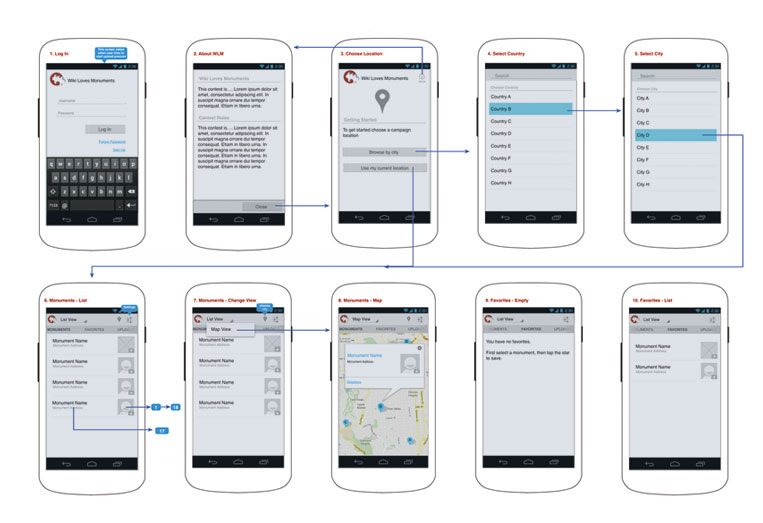

In this hypothesis, the digital breed was driven to develop an explicit vocabulary for design to enable its minting as a currency of business, which is now cashable in the boardroom. The vocabulary comes from the field now called user experience or UX. Of course that is, in some sense, what designers have always done. But labels matter: UX points to an outcome, while ’design’ appears to refer more to the activity than the result. The new label expands, and makes more tangible, the older rubrics, ‘usability’ and ‘human computer interface’.

But labels matter: UX points to an outcome, while ’design’ appears to refer more to the activity than the result.

Of course, it’s not wordsmithing alone. UX lays out its methods like a recipe. It makes the tacit knowledge of designers explicit, and re-frames designers’ instincts as a series of steps. It commandeers research from psychology’s cognitive sides. (Both the NASDAQ and Apple’s market cap have more than doubled since Daniel Kahneman‘s 2011 bestseller Thinking Fast, and Slow, which made cognitive biases part of every executive’s gab book. And since Kahneman’s 2001 Nobel, Apple’s worth has grown 180 times).

This totally rational emphasis made UX, read design, acceptable to engineers, who actually build the stuff, and may see designers as exotic anarchists. It gave business managers (a good many of them from engineering backgrounds) faith in the predictability of the design outcomes and a means to participate in the process. Design’s mystical ‘black box’ has been broken open, and made to serve new masters. Further this association with technology and business confers approval in a uniquely modern way. This all may apply only to the digital domain, but to business, what else has mattered more in the last two decades?

a UX workflow, defining customer journeys that map how a user interacts with a brand

Increasingly, businesses become more and more virtual, less physical. This makes experience, which is at heart a messy, psychological concept, easy to contain in the palm of your hand, viewed as episodes, each leaving a data trail amenable to analysis.

Design and business have followed the suits. In current design speak, UX defines customer journeys that map how a user (previously: consumer) interacts with a brand. Experience is a universal paradigm; it’s intuitive, from user experience, to imagine customer experience, the emergent new face of marketing. PepsiCo’s Chief Design Officer, Mauro Porcini, exemplifies the new argot: people “don’t buy, actually, products anymore, they buy experiences”.

Experience is a universal paradigm; it’s intuitive, from user experience, to imagine customer experience, the emergent new face of marketing.

Boardrooms have adopted design in two ways. The first is to improve design buying, making the company’s investments in, say, product design or communication, more effective. The second is to spread design culture across the company, in the role of a new approach to solving problems or seeing opportunities. To do either, designers will have to face a boardroom, peopled by stalwarts of an ancient regime, so to speak. The qualities they will need in these waters and their experiences thus far will make for a fascinating study.

____________________

First published in a slightly modified form ‘Visionary Position: Design on Top’ in Business Standard, 25 November, in Deep Design, a monthly column by Itu Chaudhuri.