kyoorius 2015 covers Itu’s life in design and the journey so far

Kyoorius Magazine interviewed Itu on his journey in design, his love for calligraphy and training young designers.

When it comes to design, personal and professional life almost seamlessly integrate for Itu Chaudhuri, lead partner, Itu Chaudhuri Design (lCD). Design became a fundamental part of his life the moment he was born into the family of two established artists. Design brought his professional and personal life together again when he got married to his firm partner, Lisa Rath, years later.

Chaudhuri grew up in a family where he was constantly surrounded by art and design. His father, the late Sanko Chaudhuri was a well known sculptor. His mother, Ira Chaudhuri, is an artist potter. Apart from being a sculptor, his father designed furniture and as a teacher, was instrumental in setting up what is now known as the Baroda stream of influence in contemporary art in India. Interestingly, his father was also into applied arts and typography.

These varied interests of his father gave Chaudhuri the idea that design is never without art and the two are related. He doesn’t see design disciplines in silos even now. He thinks that fields like architecture and graphic design are all evolving specializations and de-specializations. “”There was nothing called ‘Architecture’ or ‘Management’ about 100 years ago. It is all bits of something. Even in branding, there is convergence and de-convergence happening constantly””, he says. When he was studying architecture, he knew that architecture wouldn’t be the only thing he would be pursuing eventually.

Chaudhuri made a move to graphic design after studying architecture at the School of Planning and Architecture (SPA) in Delhi. A major credit of this move also goes to one of his mentors Aurobind Patel, a well known designer associated with various leading publications like The Economist, The Times and India Today etc. Patel gave him some of his first projects and told him that he was ‘good enough’ to do graphic design. “My graphic design education happened under him. He is an amazingly good typographer, the kind that money can’t buy. I got a taste of editorial design and typography through him. However, I wrecked it and repaired it on my own”, he says.

Even though he didn’t pursue architecture as a profession, it definitely has had a deep influence in his overall way of thinking. There is a lot from architecture, he thinks, that can be applied to every domain of design. “Architecture teaches you a way to think. The creative process in architecture is very deep. The second thing in architecture is about pragmatism and it teaches you to love constraints. The third aspect is about organization.” Today he attributes his fearlessness to learn anything to his architectural experience.

He strictly recommends that any kind of designer should follow the shadow of an architect for a fortnight, particularly when he is planning a project as it is a good way to organize ideas. “Elementarily, architecture is jumping or unjumping certain things together to boil them down to something small. This can be well applied to communication. This process is logical and it has all the depth of reasoning, constraints and can be optimized. It is not by accident that we talk about Brand Architecture,” he says.

It is no surprise that one of the main influences in his life today is Information Architecture (the art and science of organizing and labelling websites, intranets, online communities and software to support usability). “This is something we take very seriously in the way it can represent brands. We recently did the website for Indian School of Business (www.isb.edu). It was a very complex project and the information architecture for it lasted for some six months. We believed that this website is not a piece of persuasion; it’s a piece of an organization, even if there is a layer of persuasion in it.”

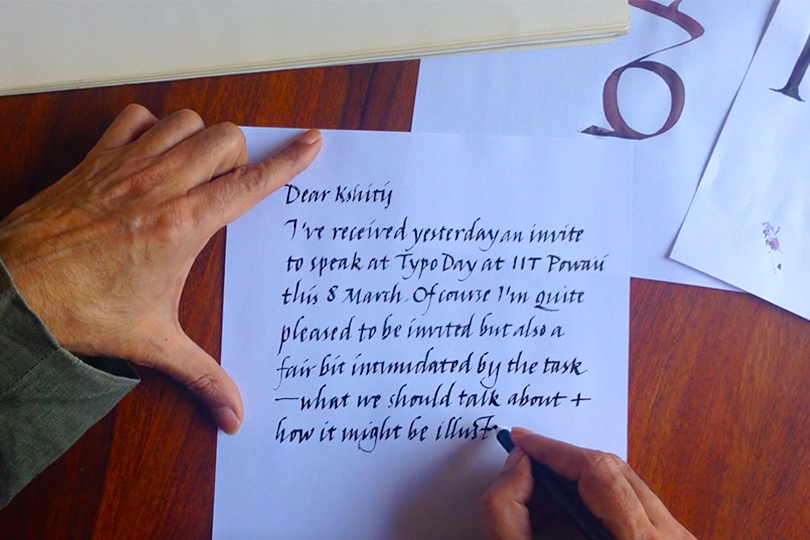

Typography is another discipline, which has a very special place in Chaudhuri’s life. We mistakenly assumed that his love affair with typography must have begun at the time when his father used to do interesting typography work. It actually was triggered by his English teacher at school who had gone to the UK for an exchange program where he learnt how to write in Italics. He says, “He would write this beautiful hand on the board with chalk and I began to copy him. I soon developed a pretty decent Italic hand which only got better with time.” This he thinks is an amazing way to understand letterform, which he now teaches.

When asked about the challenges he faced when he took the plunge to launch his own studio about 17 years ago, Chaudhuri quickly rubbishes the notion of ‘entrepreneurial challenges’. He says that one important aspect of starting out at that time was that there was nobody around to learn from and thus, he had to make his own path. There was hardly anything close to a ‘design practice’. If you didn’t want to get into advertising at the time, there was nowhere to go. Even though he takes a lot of interest in advertising, he decided not to get into it, he says. “Also, not too many people at that time knew what exactly we were doing but that’s not something that has probably changed now!”

He might have started out on his own, but today Lisa Rath is his partner at the studio and in life. She also has the ‘greater share’ now in the job of raising their 15 month old son. Rath initially joined the studio as an employee and progressively came to assume a greater and greater role as a designer and then in the organization. Today, she handles half of the business at the studio. Talking about their work relationship, he says, “She has a very different style of thinking. The way I approach branding now is unusual, creative and rigorous at the same time and Lisa would approach things with a high level of instinct. She has a great ability to get to the heart of something without taking a lot of steps on the way.”

Undoubtedly, there is a lot that he has learnt from Rath along the way as he did from his first teacher and mentor Aurobind Patel. He in fact feels that he has been lucky to have met a lot of people during his career who have taught him in various ways like Rajesh Dahiya, Aditya Pandey and Shruti Choudhary, among others. Another such ‘friend, philosopher and guide’ has been Santosh Sood, an advertising professional. “He is a very strategic person. We have worked together on some projects and are usually always picking each other’s brains,” says Chaudhuri.

When asked about some of the challenging projects that he has worked on, he says that the notion of what is challenging keeps changing for him every year. “If I look at a project I did five years ago, I usually think of it as a wasted opportunity.” He thinks that the younger generation today is far more talented than what he used to be at that age.

Though he is just being modest here, but if there was a grain of truth in that, it could be credited to the opportunities that his studio provides to the young designers. While there is no formal training for young designers at ICD, there is a much stronger informal training process, as Chaudhuri puts it. This process is tailored towards the capabilities of the individual and to develop specific drives. He says, “The three main important aspects that young designers need to learn include skills, conceptual thinking and attitude, which is basically teaching them about how to manage yourself, your inner moods and behaviour so that you are most productive. I teach that by being painfully honest about how I feel when I work.” He strictly believes in the idea of ‘learning on the job’ and gives advice to the younger generation of designers in his studio on an everyday basis.

There has been a huge change in the design space since the time Chaudhuri started out. Over the years, there has been a massive explosion of consumption of design but not without its side effects, he feels. He says, “Post 1991, a lot of things had changed. The design boom had finally started. However, with all the good things it brought (including giving backdoor entry to interlopers like me), it also brought an oversupply of underequipped graphic designers. A major reason for this is the design education system.”

Right from his SPA days, he has always been disappointed with the whole design education system. “SPA taught us everything about architecture, but not architecture. It was like we were always going in a circle in the roundabout while architecture was in the centre. This, I feel, is true for all design education.” He admits that he used to be very angry at one point with the whole education scene but over time he has become slightly sympathetic to it. His views have mellowed down a bit, but the disillusionment still continues. “The education system is a very profitable business and that is why everyone wants to start it. The most dangerous institutes are abroad, which charge a lot of money. The students get taught nothing there and then they eventually come back with misconceived notions of their own abilities.”

An idea that has been strongly propagated by him over the years is the inclusion of the planning function (akin to the account planning function in advertising) in design studios. It is basically the process of consciously, as opposed to instinctively, thinking through the particulars of a client situation. “Having very clear paths of reasoning to guide the instinct and vice versa and arrive at a clear path at which design gets built.”

“There is a very clear difference, though, from advertising in the planning function in design. In advertising, the planning process mainly involves looking for consumer insight which is usually some kind of statement/observation about a person, something which is not immediately apparent. However, just as an ad is based on insight, some people say that brand is also based on an insight. This is fine if your brand is a simple brand, but if you talk about a corporate, or organization, or an entity like a city or a country, then you cannot apply the same template. For example, Unilever cannot be based on consumer insight, but its brand Sunsilk is.”

He feels that communication is not just about the craft of design alone and designers, in their most elementary prototype, are not very good communicators. The planning function has become increasingly important as graphic designing is interlinked with communication, feels Chaudhuri. “Design isn’t completely about communication, but graphic design is a hell of a lot about communication. If you take a logo of a company, it is not necessarily about communicating, it could be more about identification and the classical training of a designer might be enough in this case. But more often than not designers are put in a job where they have to communicate and that is where this planning process comes into place.”

From his own personal experience, the result of integrating the planning function in the design studio set up has resulted in a reasoned approach to doing things. “Planning function can have a huge implication. Your clients can see, understand and then participate in the creation process. This solves a lot of problems that designers usually moan about like control (creative satisfaction). This gets solved if the design process is plugged into the client’s business process,” he says.

Chaudhuri undoubtedly presents a strong case on the planning function to make the whole design process more structured. However, he also believes in subverting structures on their head if required. “Having method doesn’t really mean that you will be a bore. Any method can be distorted any time”, he says. These two lines can easily be used to define the philosophy behind his life in design, so far.