Making Sense of Election Symbols

By themselves, symbols mean nothing. It takes prior knowledge to associate, purely by convention, a white-tipped cane with its blind owner. More connotative symbols acquire meaning by social processes. In an English storybook, a cock may announce the break of day, while its Indian cousin, the murga, may identify a certain type of tandoori joint. Each of these uses a code, a script that tells us what the once-arbitrary symbol means in a particular context.

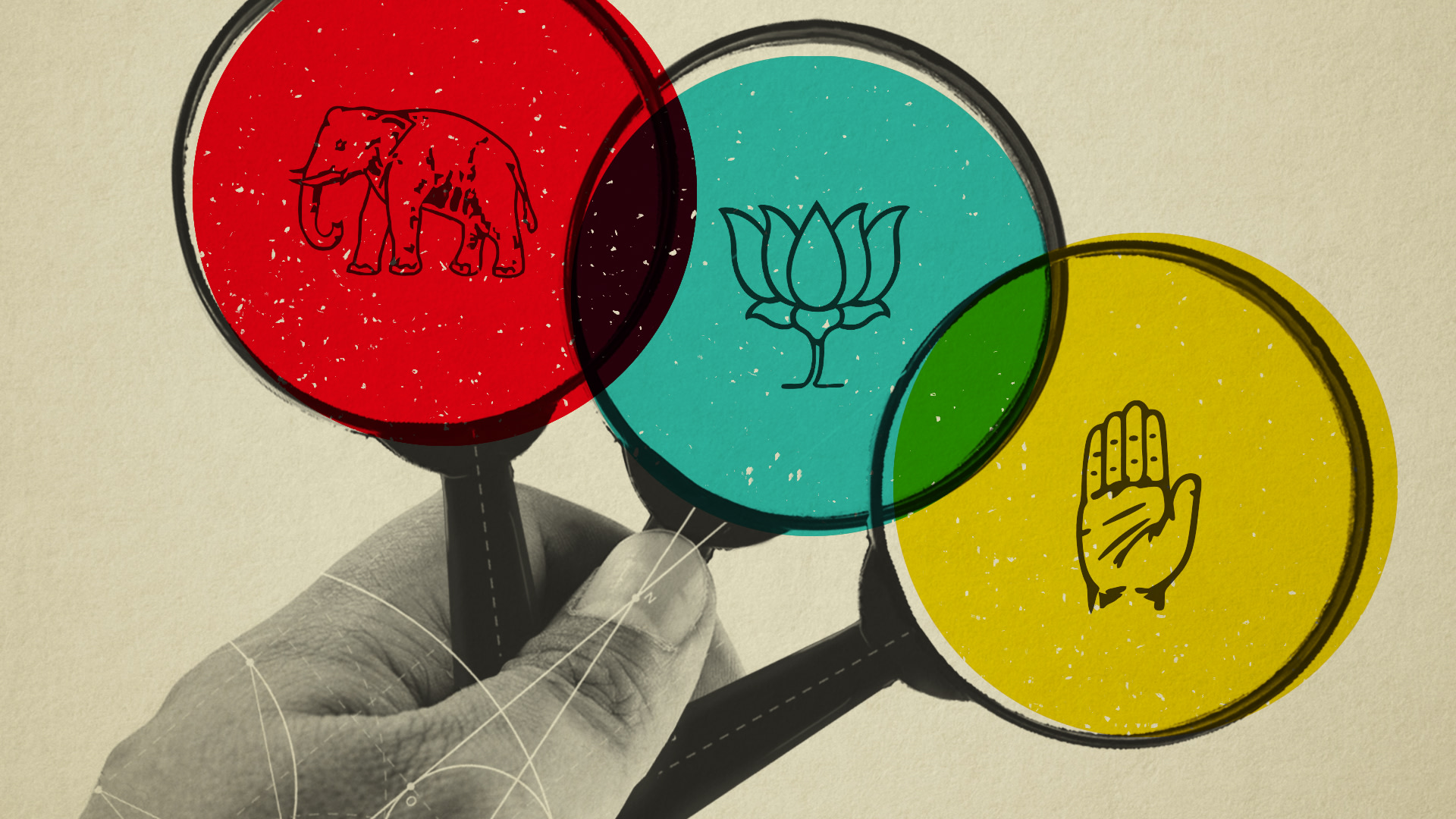

The election symbols of India, part of the democratic tumult since 1952, provide a fascinating view into this process. Their special circumstances, at first glance, seem quite hostile to symbols becoming brand elements.

Political parties do not design symbols, or truly own them. Eligible parties choose them (or apply to do so) from a library of hundreds of simplistic linear drawings of everyday household objects and animals, under conditions set by the Election Commission (EC). Its purely functional aim is to ensure that illiterate voters can identify their party on an EVM button, and in this sense an election symbol is more like an icon than an expression of identity.

we read into the symbol what we read of the organisation, and vice-versa, in a meaning-making cycle.

The paramountcy of these functional considerations turns these crude drawings into de facto party symbols, for the national parties who are allowed to reserve them (unlike state parties, which share them with parties in other states).

Yet, even in this allotment raj, meanings form. Eventually, we read into the symbol what we read of the organisation, and vice-versa, in a meaning-making cycle. Symbol and party make each other. National parties exercise choice at the time of adoption, and learn to manage and even exploit their symbols in different ways. How?

Symbol and party make each other

Even EC’s everyday-objects regime has sensible exceptions. The Communist Party of India (CPI) and Communist Party of India-Marxist CPI(M) have internationally-derived communist symbols, acknowledging their pre-existence and distinctive politics. Highly recognisable, but easy to mix up, so presumably it takes committed voters or cadres to get the right buttons pressed. The CPI(M) symbol has less detail, but it restores the hammer and the star, the latter perhaps a nod to its internationalism and a further left position than the CPI’s.

In 1977, the Congress chose its third symbol: the open hand. It is the only body part allowed by EC and was first used, with a different rendering (left), by the All India Forward Bloc (Ruikar) in 1952 and thus allows comparative comment.

As a sign, the hand has great antiquity. And extreme generality

As a sign, the hand has great antiquity. And extreme generality: to connote, it must combine with either an object (such as a hammer) or a gesture (a fist, for example) to trigger a code (proletarian protest, in this example). Its current rendering, with fingers pressed together, may evoke the blessing gesture seen in representations of gods and holy men.

Barring this faint signal, the hand’s open-endedness is its most important property. Its pre-eminence from 1947 to 1977 meant that it did not have to specify its distinctiveness. Its flexibility can, in losing times, make it look like it’s being positioned by the competition. The Congress idea, whatever it is at the time, is visible mainly by contrast, like its secularism stands out most against Sangh/Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)’s Hindutva.

In ways subtle and unsubtle, the symbols of the Bahujan Samaj Party and BJP have more religious content.

Like the hand, the lotus also has antiquity and multiple associations within specifically Asian traditions; BJP ownership makes it more overtly religious. It is pitch-perfect for BJP formulation of “cultural nationalism”, as it can foster a broadly Hindu air while averting the charge of overt religiosity (how could it, as the national flower?).

In BSP’s hands the elephant connotes power over its other popular or ancient associations.

BSP’s elephant too has positive associations for Buddhists, its original constituency, and for the Hindus it now seeks to address. In BSP’s earlier, more aggressive days, the elephant coded a new, unrelenting demographic force, not the placid animal children love. But what marks it out is Mayawati’s investment in the symbol by shrewd, if blatant, assertion of power and Dalit pride, via the Elephant Park, a monument to herself, the founder, and a triumphal regiment of elephants. In BSP’s hands the elephant connotes power over its other popular or ancient associations.

At the state level, the Shiva Sena’s bow and arrow (shared by the Jharkhand Mukti Morcha in Jharkhand) eerily mirrors its perpetual militancy against non-Marathis, the Aam Aadmi Party’s (AAP) broom has been rightly hailed as ingenious crusader branding. While both parties can only reserve them when EC recognises them as national, there’s more to being a national party.

National party symbols reflect their adoption of big, cloud-like ideas, with fuzzy edges.

National party symbols reflect their adoption of big, cloud-like ideas, with fuzzy edges. This is a necessity of national governance, the politics of which must balance a dizzyingly complex array of interests and constituents. Neither corruption, nor even local government can be AAP’s ticket to national government, nor can parochialism for the Sena. I predict that both these symbols will be dropped if these parties progress to being national contenders.

The world’s greatest election shows the strength of an ultimately human urge. Symbols may be born arbitrary, but with a little care, all but the sickliest will thrive, for we are meaning-making machines, as much as tool-making apes.

This article first appeared in the 2nd July issue of Business Standard under the column ‘Deep Design’ by Itu Chaudhuri.