Now Trending

Every year, in late December, as the solstices approach—winter or summer, depending on your hemisphere—the design-trends-for-the-next-year articles appear, as if to beat the new year deadline.

This false urgency exaggerates their significance: these aren’t catastrophic, black-swan events (wholly unpredictable—until they happen!) but slow processes already in motion. These ‘trends’ are tendentious and exist only in the eye of the observer. They are a form of navel gazing, a year-end meditation when we pause to be communitarian, and give thanks. And to indulge our need to see our biases confirmed (I told you so).

With those warnings, here’s what we saw in the Deep Design of trends-for-2019, and a speculative interpretation thereof. Call it a trend of trends.

First, digital technology is at the centre of the design conversation. Products, services and communications have converged on our devices, and most of the new ‘products’ we saw belong to this space, not only in where they operate but how we discover and evaluate them.

digital technology is at the centre of the design conversation. Products, services and communications have converged on our devices, and most of the new ‘products’ we saw belong to this space

The devices themselves are at the centre, too. The march of the mobile continues but there are signs of a correction. Design is coming to recognise the excesses of the mobile platform, a carrier that breeds a million agents vying to steal our attention, creating a society that is at its most frazzled, not to mention depressed.

The backlash will be in many forms, starting with the quick fix of Apple’s IoS and Android offering digital wellness features that essentially nudge us to be abstemious in our digital lives, helping us heal, be mindful and perchance, to sleep. The broad direction will be a kind of essentialism.

Technology will have to find ways of easing cognitive pressure. We will want fewer apps but more relevant ones, so all-in-one apps may not be the answer. Innovation is required, to save us from the excesses that made it succeed.

Technology will have to find ways of easing cognitive pressure. We will want fewer apps but more relevant ones, so all-in-one apps may not be the answer. Innovation is required, to save us from the excesses that made it succeed.

A virtual assistant, Google Home Mini

The answers will have to be found in our daily lives, at home, on the road, and at work: the data that we capture, use and convey, and its potential for tyranny as well as for being misinterpreted and thus becoming more noise than signal.

Outside the digital world, we will be drawn to products that tread lightly on our brain space, and the earth. Younger consumers are already sensitive to waste in packaging for example, paying more for sustainable, re/up-cyclable products. This dovetails with a long-running yearning for simplicity. In fashion, for example, the call will be for more functional wear, and versatile enough for work and leisure.

Fewer products, with general applicability will be the ask all over the home and workspace (and the two may blur). Functionality will be defined as fewer features done better, trading absolute capability for less space, economy, and cognitive ease. Indeed, the support for de-cluttering is a popular theme, and a mini-industry. Marie Kondo, a best selling Japanese author and star of a Netflix show, teach a legion of followers to de-clutter and do with less.

Fewer products, with general applicability will be the ask all over the home and workspace (and the two may blur). Functionality will be defined as fewer features done better, trading absolute capability for less space, economy, and cognitive ease.

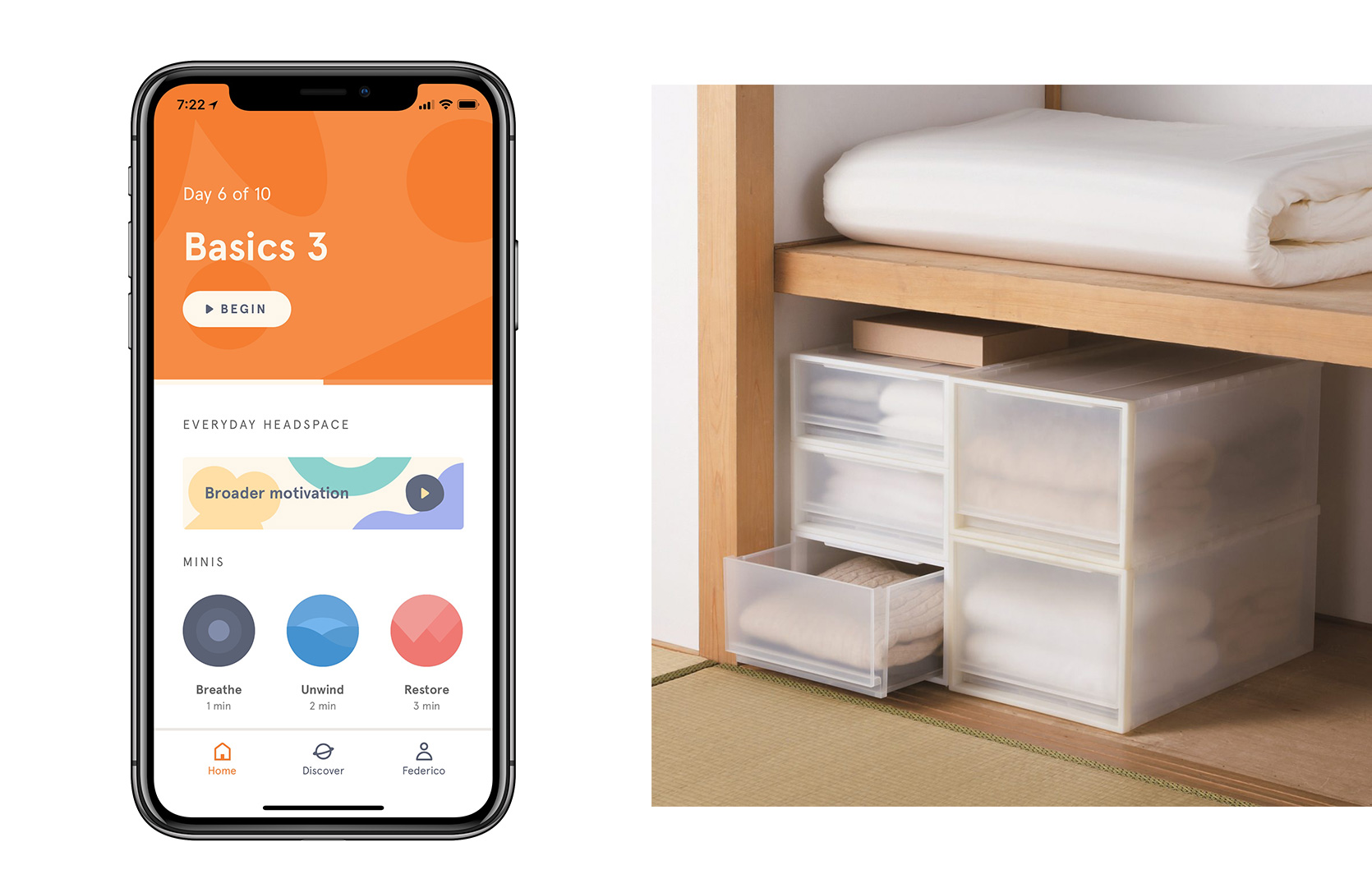

(L) Headspace, a mindfulness app, (R) minimal organisers by Muji

Perhaps this will extend to ‘smartitecture’, or the design of repurposable spaces rather than purpose built ones. Digital sockets will populate homes, public spaces and workspaces. A conference room forms where space exists, and the required facilities will appear as needed. The formality of chairs or decor may be irrelevant, and agility will be the rule. A charging point for mobiles built into airport lounge chairs is a tiny step in that direction.

In like vein, expect automation at the city level. It’s bound to strike a municipality that while it’s good not keep street lights on at night for general safety, they can stay dim, or be off, and light up when a car is sensed. A lone driver on a long causeway at 3 a.m. might find the street lights switching on in her windshield view and switching off in the rearview mirror. An Internet of lamp-posts, so to speak, while the IoT (internet of things) is still not ready as a consumer application.

This will require governments and citizens sharing data, and while it raises irksome issues, the prediction is that many will welcome it for an IoT that really works (not a thing, yet) and other services. Some government data will become available. Deep Design bought an air quality monitor which is controlled by an app (of course) which also accesses government pollution data. The reverse too, why not—tell the government about your smoggy street.

The tension between private and public is a creation of the tech decades, starting with the personal computer, going on to personal everything. The social consequences of this are many, but expect extreme ‘mass personalisation’ to trend in more and more services.

Meanwhile the trend of brands looking like and speaking to consumers as one of them continues and authority as a communication position continues to be more and more untenable. Apple pioneered the trend with its name and its folksy Californian demeanour, a refreshing contrast to the tech companies of the day. But today Apple comes across as an uber-designed high priest, its hardware decked out in pristine materials. Expect tech brands to be less Apple and more Lyft, the very millennial ride sharing service whose sense of colour and playful imagery make it a likelier standard of the new attitude. Not coincidentally, Lyft has bet heavily on design, appointing six designers to CXO roles. That’s another trend that’s likely to continue.

Expect tech brands to be less Apple and more Lyft, the very millennial ride sharing service whose sense of colour and playful imagery make it a likelier standard of the new attitude. Not coincidentally, Lyft has bet heavily on design, appointing six designers to CXO roles. That’s another trend that’s likely to continue.

(L) ride sharing service, Lyft, (R) personalised curation by Netflix

Finally, it appears that the influence of tech companies on design for the rest of us is also at a zenith. Many of them imitate each other, with a super-clean, minimal, hyper-functional identities, but the ‘startup look’ may have spilt over everywhere, from cosmetics to milk. You should bet on a correction this year, with brands showing more individuality and a larger emotional repertoire. Conversely, expect apps to be warmer and quirkier, in ways beyond the friendly/chatty personas that all of them adopt to the point that they blur into one (oops, something went wrong).

Community, mindfulness, and warmth: a hopeful start to the new year.

____________________

First published in a slightly modified form ‘Now Trending’ in Business Standard, 18 January in Deep Design, a fortnightly column by Itu Chaudhuri.